Why commerce platforms keep breaking, and what a different architecture actually looks like

In this opinion piece:

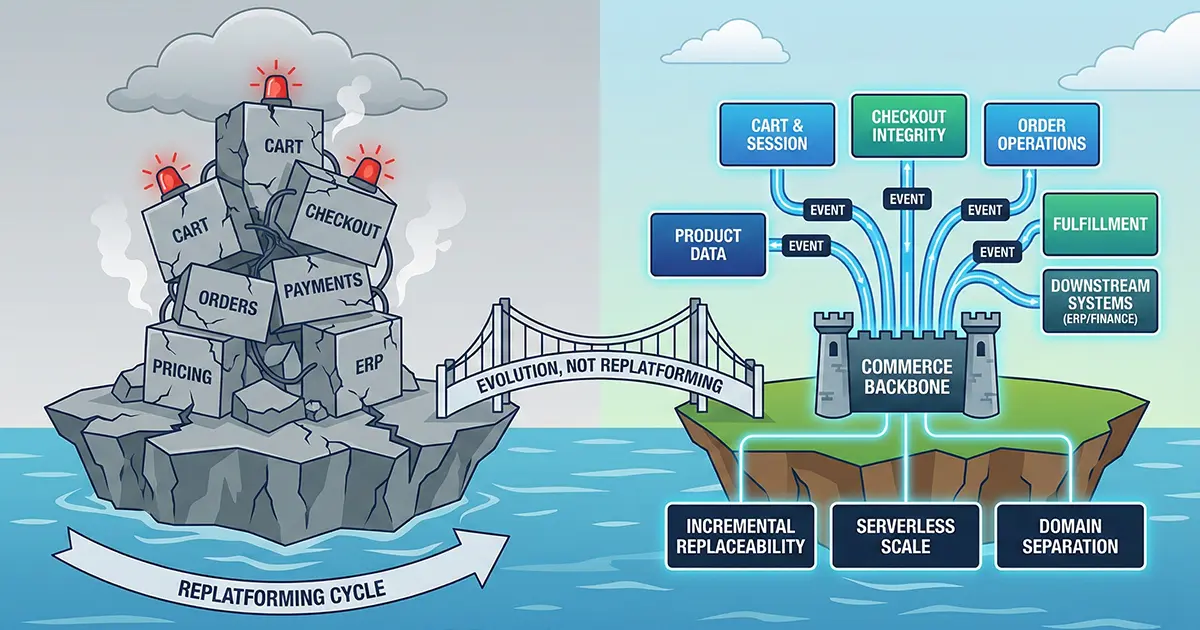

Most commerce platforms fail because they are built as tightly coupled systems that cannot adapt as businesses change. John Osvald explains his take on why a backbone built around lifecycle stages, domain boundaries, and event-driven architecture, replaces repeated re-platforming with incremental change.

I have spent a number of years building, operating, and rethinking commerce platforms. Not as a consultant parachuting into post-mortems, but as someone accountable for what happens when the platform meets reality, when traffic spikes, when new markets launch, when the business model shifts and the system that was supposed to support growth becomes the thing blocking it.

What follows is not a product pitch. It is an attempt to articulate what I have come to believe about how commerce systems should be built, where the industry keeps making the same mistakes, and what it looks like when you design for change rather than for a single moment in time.

The replatforming trap

Most commerce organizations I have worked with or spoken to have been through at least one replatforming. Many have been through two or three. The pattern is almost always the same. A platform is selected based on feature checklists and short-term fit. It works well for the first year or two. Then the business grows, new markets, new channels, new payment requirements, new regulatory demands, and the platform that seemed capable starts resisting change. Customizations pile up. Integrations become fragile. The cost of small changes begins to approach the cost of large ones. Eventually someone proposes a new platform, and the cycle begins again.

The assumption behind each cycle is that the current platform was wrong and the next one will be right. But the real problem is usually not the specific platform. It is the assumption that any single system, selected at a point in time, will continue to serve a business whose needs are guaranteed to change.

The question worth asking is not “which platform is best?” but “how do we build a commerce foundation that does not need to be replaced every time the business evolves?”

Where complexity actually comes from

Commerce looks simple from the outside. You have products, prices, a cart, a checkout, and an order. But anyone who has operated a platform at scale knows that the real complexity lives in the boundaries between these things. What happens when a price changes while a cart is open? What happens when inventory is reserved at checkout but the payment fails? What happens when an order needs to be partially refunded across two payment methods and a gift card?

These are not edge cases. They are daily realities for any merchant operating at meaningful scale. And the way a platform handles them, or fails to, is determined almost entirely by how responsibilities are separated in its architecture.

When product data, pricing, inventory, checkout, payments, orders, and accounting are tangled together, every change becomes high risk. A promotion engine that reaches into order logic. A checkout flow that assumes a specific payment provider. An order model that encodes the structure of a single ERP. These couplings are invisible at launch and damaging at scale.

The alternative is to treat each of these as a distinct domain, with explicit boundaries, clear inputs and outputs, and predictable transitions between them. Not as an academic exercise, but as the only way to keep a growing commerce operation manageable.

What “scale” actually means

When vendors talk about scale, they usually mean throughput, requests per second, orders per minute, transactions per peak. Those things matter, but they are only one dimension of a problem that is fundamentally multi-dimensional.

Operational scale is the ability to add markets, channels, legal entities, and providers without duplicating your platform or your team. Financial scale is the ability to grow revenue without your technology cost growing faster. Technical scale is the ability to handle peak traffic without pre-provisioning infrastructure or firefighting capacity.

A platform that handles Black Friday traffic but requires six months of engineering to launch in a new country has not scaled. A platform that supports forty markets but costs more per order than the margin it enables has not scaled. Real scale is the combination of all three, and it comes from architecture, not from adding more servers or more people.

Why events change the game

One of the most consequential architectural decisions in any commerce system is how its components communicate. The traditional approach is synchronous, request-response integration, one system calls another and waits for an answer. This is intuitive and easy to reason about in simple cases. But at scale, it creates a web of dependencies where a failure in any single system can cascade across the entire stack.

Event-driven communication inverts this model. Instead of systems calling each other, they publish facts about what has happened, and other systems consume those facts at their own pace. A price change is published. A cart update is published. An order creation is published. Downstream systems, ERP, warehouse management, analytics, finance, can process these events independently, retry on failure, and operate at their own speed.

This does not eliminate complexity. But it makes complexity explicit and bounded. Failures become isolated rather than cascading. Systems can evolve independently. And the operational cost of integration goes down over time rather than up.

The lifecycle as a design principle

The single most important structural decision I have seen in commerce architecture is how the lifecycle is modeled. By lifecycle, I mean the progression from raw commerce data, products, prices, inventory, through the shopping experience, cart, session, context, through the transactional boundary, checkout, payment, shipping, into the operational phase, orders, fulfillment, returns, refunds.

When these stages are clearly separated, several things happen. Teams can own stages independently. Changes to checkout logic do not ripple into order management. Downstream systems receive stable, normalized data regardless of what happens upstream. Testing becomes focused. Debugging becomes tractable. And most importantly, individual components can be replaced or upgraded without requiring a full replatforming.

When these stages are blurred, when the cart is also the order, when the checkout encodes assumptions about the ERP, when pricing logic is scattered across three systems, every change touches everything. This is how platforms that looked simple at launch become impossible to maintain at scale.

The false promise of “future-proof”

I have seen the phrase “future-proof” in hundreds of vendor presentations and RFP responses. It is well-intentioned but misleading. No one can predict what a business will need in five years. No architecture can anticipate every regulatory change, market expansion, channel innovation, or shift in consumer behavior.

The durable alternative is not to predict the future but to avoid encoding assumptions that will have to be removed when the future arrives. This means separation of concerns. It means configuration over custom code. It means the ability to replace any single component, a payment provider, a shipping integration, a pricing engine, without rebuilding the core.

The goal is not a platform that never changes. It is a platform that changes well, incrementally, predictably, and without forcing the entire organization through a migration every time.

The space between SaaS and composable

The commerce technology market has, for the past several years, been roughly divided into two camps.

On one side, you have fully managed SaaS platforms, fast to launch, opinionated, and effective for straightforward use cases. They excel at getting a merchant to market quickly. But as complexity increases, multiple markets, multiple legal entities, custom pricing logic, non-standard fulfillment, they begin to resist rather than enable. Their simplicity becomes rigidity.

On the other side, you have fully composable architectures, maximum flexibility, full control, best-of-breed everything. In theory, you can build exactly the system you need. In practice, the integration burden is large. You need a team capable of orchestrating dozens of services, managing contracts between them, and maintaining coherence across a stack that no single vendor owns. The total cost of ownership is often higher than anticipated, and the time to value is measured in quarters, not weeks.

Most merchants do not belong cleanly in either camp. They need more control and flexibility than a simple SaaS platform provides, but they cannot afford, financially or organizationally, the overhead of a fully composable stack. They need something in between, a platform with opinions where opinions matter, and openness where openness matters. A backbone, not an all-in-one suite, and not a bag of parts.

What a commerce backbone looks like

This is the space where I have spent most of my recent work, and where I believe the most important innovation in commerce infrastructure is happening. The concept is straightforward, even if the execution is not.

A commerce backbone is a platform that owns the core operational lifecycle of commerce, data normalization, cart and session management, checkout integrity, order creation, and order operations, while deliberately not trying to own everything else. It does not try to be your CMS, your search engine, your marketing automation platform, or your ERP. It provides the stable, event-driven, API-accessible center that those systems integrate with.

This is the approach we have taken with Brink Commerce, and it is the result of years of learning what works and what does not in real commerce operations.

Brink enforces a clear lifecycle. Commerce data flows in, is normalized, and feeds into cart and session management. The cart transitions into a checkout, an immutable transactional boundary where pricing, inventory, discounts, tax, payment, and shipping are frozen and validated. Once checkout completes, a normalized order is created with a stable, provider-agnostic structure that downstream systems can rely on. From there, order operations, deliveries, cancellations, refunds, compensations, are handled with explicit, auditable actions.

Every transition between these stages is explicit. Every significant state change is communicated through events. And every domain, product data, pricing, inventory, discounts, orders, is treated as a separate concern with clear boundaries.

How this changes things in practice

For merchants operating across multiple markets, channels, and legal entities, the practical implications are significant. Behavior is driven by configuration, different pricing per market, different payment providers per channel, different tax rules per legal entity, without duplicating the platform or forking the codebase.

Replatforming is replaced by incremental evolution. Because each domain is separated and communicates through events, individual components can be replaced over time. A payment provider can be swapped without rewriting order logic. A PIM system can be replaced without affecting checkout. An ERP integration can be modernized without touching the cart.

Total cost of ownership becomes a function of architecture rather than vendor negotiation. Serverless infrastructure means you pay for what you use, not for what you provision. Microservice architecture means individual domains scale independently, you do not need to scale everything to handle a spike in one area. And event-driven integration means downstream systems are not bottlenecked by synchronous API calls during peak traffic.

For system integrators and implementation partners, the model provides clear boundaries. Brink handles the operational core of commerce. Partners deliver value through frontend experiences, ERP and WMS integrations, business-specific logic, and market rollout strategies, without needing to reimplement cart, checkout, or order management.

What a backbone should not do

Equally important is what a commerce backbone should not try to do. It should not own product enrichment or content modeling, that is the job of a PIM or CMS. It should not own financial accounting, that is the job of the ERP. It should not dictate the frontend experience. It should not try to be a warehouse management system.

The temptation to expand scope is constant in platform development. Every customer request feels like a reason to build one more thing. But every capability you absorb into the core is a capability you must maintain, version, and support indefinitely. The discipline of a backbone is knowing where to stop, and making sure the boundaries are clean enough that other systems can do their jobs well.

The commerce future this enables

I do not believe in predicting what commerce will look like in ten years. I do believe that whatever it looks like, the organizations best positioned to adapt will be those who did not bet everything on a single vendor’s vision of the future.

The approach described here, lifecycle separation, event-driven integration, domain boundaries, serverless scalability, incremental replaceability, is not about building the last commerce platform you will ever need. It is about building a commerce foundation that lets you change your mind. About payment providers. About frontend frameworks. About which markets to enter. About how fulfillment works. About what commerce even means for your business next year.

That is not a promise. It is an architecture. And in my experience, architecture outlasts promises every time.

John Osvald

Want to know more about modern commerce?

Get in touch with us to get the discussion started?

Get in touch